(Josef Koudelka)

|

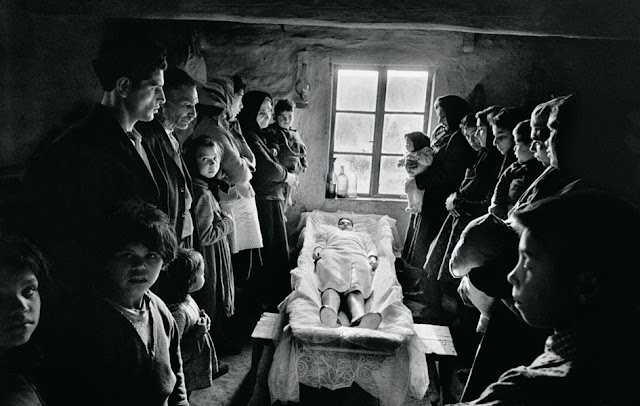

| Josef Koudelka. “Funeral wake”, 1963 |

I am coming to the conclusion of the first ten photographs that I loved the most.

Inevitable that I have to talk about

Josef Koudelka, the Czech photographer born in 1938.

Why is it inevitable? Because his

book “Gypsies” was one of the first I bought and remains, for me, the most

beautiful photography book, the one to have absolutely.

|

| Josef Koudelka |

His story is well known, of how a

phone call turned his life upside down.

“The phone

rings at 4 in the morning, a friend screams: “The Russians have arrived.” […] I

understand that something is happening. I get dressed quickly, I take my camera

and all the films I have left, I had only returned the day before from Romania,

where I had been to photograph the gypsies.”

He is 30 years old, that August 21,

1968. Take the iconic photo on the deserted esplanade of San Vanceslao, on

August 22, with his watch in the foreground to make it clear what time it was.

200 rolls of films will be released

which will represent one of the greatest reports in history on the bloody

repression of the Prague Spring.

The rolls left Prague hidden in the

suitcase of a doctor who had come to the city for a congress; they reached the

Magnum agency and ended up published in the periodical “The Sunday Times”

signed only with the initials P. P. (“Prague Photographer”) to avoid

retaliation against him and his family.

It was thanks to Magnum that he was

able to leave Prague and live in exile for 20 years, without being able to tell

his parents that those photographs that were traveling around the world and

winning prizes were his photos.

They will die without ever knowing.

|

| San Vanceslao Square, 1968 |

It was then that he returned to his

project on the gypsies of central Europe, because as it is often said Koudelka

was nomadic at heart.

The anecdote that Alex Webb tells is

emblematic:

“A few

years ago I was sitting on the subway with Josef Koudelka, whom I had not seen

for several years. Suddenly Josef leaned forward and grabbed my shoe, turning

it to look at the sole. With his direct way of doing, typical of Czech culture,

he wanted to make sure that I had walked enough – and therefore photographed

enough.”

Koudelka's personality is

fascinating and complex, as mysterious as the St. Charles Bridge in winter, for

anyone who has visited Prague and understands what I mean.

The exile marked him deeply but made

him capable of a different way of seeing.

“When you live in place for a long time, you become blind because you no longer observe anything. I travel so as not to go blind.”

It is during exile that he returns

to work on the reportage on the gypsies, as I said.

The first version of 1968 failed to be printed in 1970 because he was forced to leave Prague.

In Paris, he goes back to those

photographs: 60 images taken in the gypsies’ camps of Slovakia between 1962 and 1968, released in 1975 with the title

“Gitans”.

The current version, which can be

found in the bookstore, is the one enlarged to 109 photographs taken in the

former Czechoslovakia, Romania, Hungary, France and Spain between 1962 and

1971.

|

| 1969 |

It's a poignant book, with black ink that seems to stain the fingers, grainy and alive.

He is not interested in representing

the life of gypsies in a didactic way (before the term Rom entered the

vocabulary, more polite but less truthful), or making a social report.

“I wanted

to talk about life, what's more universal? I didn't want to make a historical

documentary but to talk about existence, from children to death, this

interested me.”

This makes it a mythical book, at

least in my eyes; like when you read the Odyssey, the “Brothers

Karamazov”, the “Don Quixote”. You know you have something in your hands that

is out of ordinary.

Each photograph is full of life,

emotions, total absence of the slightest prejudice.

He lived there with the gypsies, he

follows them at their festivals, in the chariots during their journeys, in poor

and dirty houses, in front of naked, wild, cheerful bodies, splendid children

and elderly people with wrinkled skin like fossils.

Always photographing with an

atypical wide angle, which made him tremble when Cartier-Bresson asked to show

him his photos, because he knew that the French master hated the wide angle.

But Koudelka did not use it at a

distance to enclose large spaces, but in close contact with people, to include

every possible emotion and smell.

It is no coincidence that

Cartier-Bresson chose two photos for him, one of the man in handcuffs and the

other of the wake of 1963.

This is the photo that Koudelka

loved most, and I totally agree and have shown it in every workshop I have held

on the Masters of Photography.

|

| 1963 |

Anyone who photographs knows how

difficult it is to be invisible to others, to be shadows of the subjects that

are photographed.

We are there, with our presence, the

camera and its sounds, our gaze that weighs.

This happens in accordance with the

level of intimacy we are able to establish with the people in front of us. The

more distant and “unknown” we are, the more it will be impossible to act

discreetly, silently.

But if we manage to enter the

private area that everybody has around it, if we manage to become part of the

family, we cease to be photographers, and we become of the same flesh holding a

camera as it could be a cigarette or a fruit or a toothpick.

We are no longer noticed.

|

| 1967 |

Only in that moment does the photo

become unique, a wonderful symbol of this sharing common presences.

This should be explained because, to

non-photographers, it may seem like a simple photograph of a wake, nothing transcendental.

Therefore it must be said and

repeated that this is a photograph of an incredible difficulty, because

although the moment is so private and full of pain, crowded with suffering,

there is not a single adult person who turns to look at Koudelka who takes the

picture: as if the sound of his camera and his presence were like the tears and

sighs of the people in that room.

Only children look at it, but you know, children are not part of our world, they have their own particular dimension with rules of their own that only Saint-Exupéry has been able to describe perfectly with “The Little Prince”.

It is a magical, unsurpassed photo.

That you observe it once, ten, a

hundred times and sighs of such beauty.

And you think no one will ever be

able to photograph gypsies better than Koudelka did.

But this doesn't have to be a scythe

that cuts the leg of our ambitions.

Rather an invitation to aspire to

one day be able to take photographs that come close to these, to achieve total

empathy with those who are completely far from us.

To open your eyes.

Not to be blind.

|

| 1967 |

Josef Koudelka: “Gypsies”

(Contrasto, 2011)

Mario Calabresi: “Ad occhi aperti” (Contrasto, 2013)

I love the last phrases.

ReplyDeleteTo open your eyes.

Not to be blind.

Thanks for sharing.

Interesting.

Thanks a lot 🙏

DeleteA street photographer...is the one that makes other person think...when looking at their photos.

ReplyDeleteAnd one that brings up a specific feeling, story or idea...and you are one of them...nice sharing.

Thanks a lot😊

He is not just a street photographer, he is a Master 😊

DeleteThank for this good article. I wish to learn more.

ReplyDeleteThis is my intention 🙏

DeleteNot only open the eyes,

ReplyDeletebut also open my mind. Good sharing.

Thanks a lot ☺️

Delete