|

| Grace Nono. Rome, July 2013 |

Almost twenty years have passed since I began to frequent the Filipino community in Rome and to get to know their music; it was the pre-social era, I mostly spent my time on a file-sharing site randomly downloading songs from Asia, including many from the Philippines, without understanding a single word, but for me, music has always been more a question of the gut that is not intellectual: what must please me and strike me are the sounds, the melodies, the voices more than the words, so the misunderstanding of the texts have never been a great impediment. This is how I got to know the music of Grace Nono, an artist not too famous among the Filipinos themselves, but with a very warm voice and ethnic melodies.

It so happened that, in July 2013,

Grace was a guest in Rome of a dear friend of mine who, knowing my admiration

for the singer, invited me to meet her. We spent pleasant hours in the

beautiful house of my friend Chato, immersed in her wild garden that seemed to

be in a Philippine forest, also taking the opportunity to take some portraits

of Grace.

She had brought her latest book

along with some music CDs and it was her gift for us. I would then have given

her, thanks to Chato who was returning to the Philippines, one of her portraits

enlarged and framed with a dedication.

These are the magical encounters

that make me thank my passion for Photography every day.

|  |

That book has been in my mind for years; I often had the intention to talk about it but there was never the right opportunity.

But looking at my last two posts, it

seemed to me that the time had come. What does the story about Cambodia, the

Korean Pansori, and Grace Nono's book have in common? The spirits.

The Cambodian story was almost a

real ghost story, while, regarding the Korean musical recital, I mentioned Jin

Chae-seon, considered the first woman to have performed in Pansori, born in a

fishing village from a shaman mother.

It is therefore not difficult to

imagine what the theme of Grace Nono's book is. Not really the spirits but

certainly the link with their beyond-world.

It is entitled: “Song of Babaylan –

Living voices, medicines, spiritualities of Philippine ritualist-oralist-healers”,

published by the Institute of Spirituality in Asia, in 2013.

A full-bodied tome of nearly 400

pages, full of photographs and lyrics of sacred songs. Therefore it's

impossible for me to talk about it in depth, but I will fly as close as a

dragonfly on the surface of the water.

Through this work Grace also talks about herself as a woman and as an artist. And from her childhood, you understand how she was predestined not only to art but also to one day write this book.

|

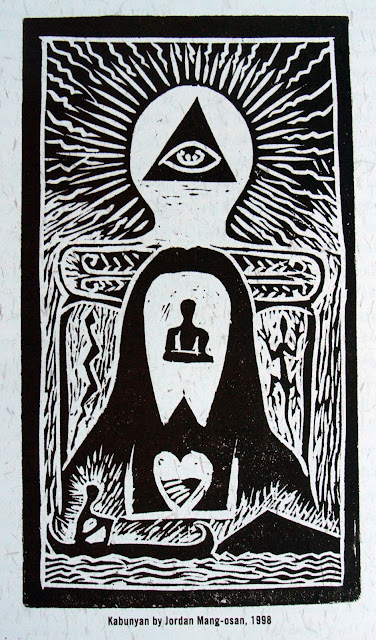

| “Kabunyan” by Jordan Mang-osan, 1998 |

First of all, who are the Babaylan?

Quoting the anthropologist and

scholar of popular traditions Francisco Demetrio, Grace Nono reports the dense

nomenclature referring to the different etymologies of the term according to

the geographical area to which it refers.

From the bailan or balian

in Visaya, Cebu, Bohol, Palawan and Northern Mindanao, babailan in

Negros, balyan among the Negritos; also among the Dayak of Borneo the

priestesses-shamans are called bailan, while in Kelantan, in Malaysia,

they are called belian bomor. The list of nomenclature continues.

Tracing the use of the term babaylan from 1700 to the nineteenth

century, in dictionaries compiled by the Spaniards, Gace Nono reports among the

first definitions that of Father Juan Felix de la Encarnacion in his

Eighteenth-century Diccionario bisaya-espanol: “sacerdotisa entre los

idolatras”, or the woman who conducts magical rituals among those who

worship idols. The fact that the term priest or priestess was used means that

it could have been both a male and a female role, although there are those who,

like the psychologist and art historian Luciano Santiago, push the idea that

the term babaylan comes from the Tagalog “babae lang”, meaning

“purely female, only woman”.

However, what unites every

definition, in every dialect of the different areas of the Philippines, is the

reference to the one who works in contact with the anito (the spirits),

celebrates sacrificial rituals to the diwata (divinities) or to the umalagar

(the spirits of the ancestors). It is important to note that the terms bailan

or balian do not exist in Tagalog, so it's strong the idea that the term

babaylan was introduced in the Philippines from Malayo, or some other

Indo-Malay language.

|

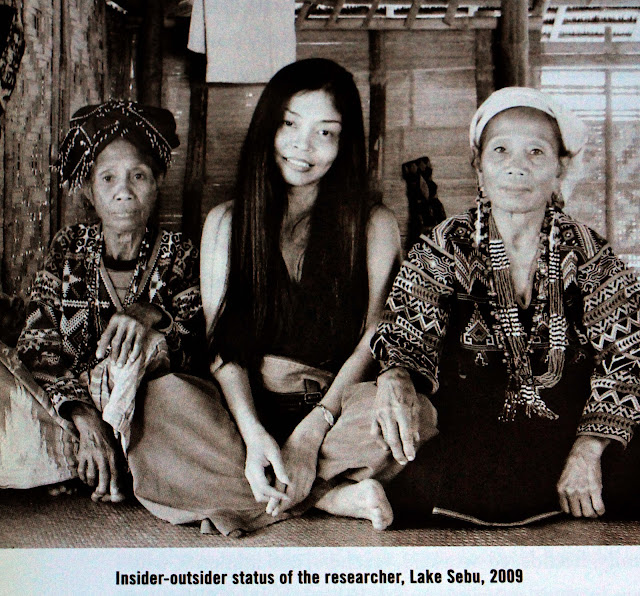

| Lake Sebu, 2009. Photo by Maria Todi |

Grace Nono's work analyzes the babaylan

of different ethnolinguistic groups, the experiences, and songs of oral

healers, following a path that goes back to the roots and ancestors and at the

same time in the depths of the soul where there is the meeting between human

and divine, not in the dogmatic and cerebral way of classical religions, but as

part of the life of the people who live it, with their myths, proverbs, and

oral codes that are handed down from generations. The fear of losing this

enormous unwritten heritage prompted Grace to work for seven years on this

book, helped by ISA – The Institute of Asian Spirituality, because as Reverend

Christian Buenafe, Commissioner General and ISA member in the introduction of

the book, healing is what we need in these times of division, fractures and

psychic distress, and studying traditional healers helps to understand who we

are.

This is how Grace opens the book,

recounting her childhood, about the fact that she finished this long job shortly

after the death of her beloved mother Ramona; and that the writing, following

the long study, was the medicine and cure for her for the deep pain of this

loss.

She recounts an episode from her

childhood, in the city of Bunawan, in Agusan del Sur in northeastern Mindanao,

south of the Philippines: it was evening and she was lying sick in bed on the

top floor of their house when she heard her father Igmedio call her name from

the courtyard below. Except that he was not addressing her, but shouting her name towards

the night sky; when later Grace asked him what he was doing, her father replied

that he was invoking her soul to come back so that she could heal.

The father, of Ilocano origin, was

not a babaylan, but his life was part of that belief system whereby spirits

were able to capture souls and babaylans could deal with them to return

those souls by healing from disease.

Grace proudly claims the origins of

indigenous descent, from her mother, a native of the Camiguin Island, once

inhabited by the Proto-Manobo of Mindanao, and from an Ilocan father of Nueva

Ecija in central Luzon, from the north to the south of the Philippine. She grew

up with a strong Catholic upbringing, forced by her mother to sing from child,

but when she expressed her desire to become a priestess, her priest replied

that in the Catholic church, women could not become priestesses.

Grace, therefore, enrolled in the High

School of Art in Luzon, where she learned the history of the babaylan, filling

her 15 years with enthusiasm, so much so that she became the subject of her

graduation thesis. After college, instead of becoming a teacher like her

mother, she started her career as a singer, initially copying the Western style as a “good educated Filipina”, she writes with irony. But it didn't take long

for her to realize how foolish it was to copy a style that wasn't quite right,

and it was on a return trip between the mountains of the provinces of Davao and

Bukidnon that she came into contact with babaylan and songs she was completely

ignorant of their existence.

This led her to graduate from the

University of the Philippines with a thesis on oral traditions and to become

the symbolic singer of the deep ethnic and mystical traditions of the

Philippines.

|  |

The book collects ten babaylan

stories from across the island, with interviews and some of the songs

transcribed. Each of these shamans has her own ritual song.

Reading the interviews is absolutely

interesting, and it is impossible to account for it in this short piece of mine.

Most of the time they are elderly

women, with some slightly younger students who will inherit that oral knowledge

that would otherwise be lost.

Like the first babaylan

interviewed, andadawak Aragoy Tumapang, an expert in Dawak singing in

Tabuk, the capital of the Kalinga region, in the Cordillera of Luzon, in the

north of the Philippines. With her is Gammay Ammakiw who is learning the Dawak

technique in healing rituals.

As she tells Grace, when she

reaches a trance (paramag) during the Dawak's performance, her body

begins to lose sensitivity and expands into something greater than herself:

“Maybe my arungan (the guardian spirit) enters me, making me bigger and

stronger than I really am.”

With this force, they can hoist and

throw even huge pigs onto the ground, possessed by a supernatural force that

helps them heal sick people.

This is a short excerpt from a Dawak

song called “Aragaoy's Owab”:

with your strong powers?

Be on your way now,

go far into the mountains

if it is you that caused

this child's illness.”

|

| Image of a babaylan in Puerto Princesa. Palawan, 2006. Photo by Charles Wadang |

Or, going down to the south of the

Philippines, in the autonomous Islamic region called Bangsamoro, Datu Odin

Sinsuat in Maguindanao, with the incredible story of the patutunong Babo

Samida expert in Daging singing. This area has always been the stronghold of

Islam in the Philippines, ever since they opposed the Spanish colonial

government in the 1600s, coalescing with the Maranao, Tausag, and other Islamic

groups.

In this context of strong opposition

to the predominant import culture, the preservation of the ancient ancestral

traditions assumed an added value, also because for decades the dominant

religion of Maguindanao was a sort of folk Islam, which however will

become more and more orthodox over time, thanks to the influence of the ustadz,

the teachers of Islam.

And precisely one ustadz is the

husband of Babo Samida, and this will place the two of them in constant

contrast, where the husband rejects everything that is considered pre-Islamic,

but on the other hand, the wife is not absolutely willing to give up to her

beliefs that go back in time and are anchored to ancestral beliefs, while

remaining in the groove marked by Islam, because as the elderly healer tells

us, spirits are creatures of Allah and must be listened to. Thus, while the

orthodox Islamic religious community boycott ritual festivals such as dundang,

Babo Samida refuses to treat the ustadz who search her out when they fall ill.

As Faisal, a patutunong

novice of Babo Samida, says: “Modernity is the other thing that has contributed

to the marginalization of our traditions. Because traditions are seen as

backward, families have stopped teaching our traditions to the young. Hence,

many in this generation no longer understand these things.”

Being a patutunong, a healer,

was never her will, says Babo Samida, but Allah's will and she is happy to be

able to help heal people, as well as pass on the ancient customs of the people

to her.

This is a beautiful Daging

invocation dedicated to Abraham.

“In the name of Allah,

the Highest, and of Allah's prophet...(with) this boat

renamentaw that now pushes forward,

it is my deep and clear desire

that you will take to

the vast ocean, all

illness and heartbreak

among the prophet's followers.”

|

| Maguindanao patutunong Samida Tato, Quezon City, 2005. Photo by Grace Nono |

|

| Sapia Mama (center) for whose healing (as well as her grandfather) the dundang ritual was performed. Datu Odin Sinsuat, Maguindanao, 2009. Photo by Grace Nono |

After Babo Samida, Grace reaches

Batangas and the subli matremayo Ka Mila of Catholic tradition, Manobo babaylan

Lordina “undin” in Agusan del Sur, and others, each with its own story and

songs.

There is also a male presence, as

for the Ibalaoi mambunong Henio Estakio, of the Ibaloi ethnic group in

Baguio City, in the north of the Philippines.

Obviously, this is a topic that may

be of more interest to Filipinos who perhaps ignore this part of their

tradition that remains in the shade.

But I believe that it can also be

important for each of us.

After all, as Grace Nono wrote, this

long work of years was a way of getting to know her soul in depth, and at the

same time heal the wound of the loss of her beloved mother.

These songs are addressed directly

to the spirits, create an invisible link between them and us, speak to that

dark area which – in the belief of these healers – is the cause of our

diseases.

|

| Minang Saling in Tagbanua babaylan garb. Aborlan, Palawan, 2006. Photo by Charles Wandag |

|

| Cebuano-Visayan sinuog leader/ritualist Estelita “Inday Titang” Diola. Mabolo, Cebu City, 2006. Photo by Grace Nono |

I think this is the most important

point: do not cut or ignore that dark and mysterious part that resides within

us; dialogue with it is the way to avoid falling victim to its aggressions.

As Freud's psychoanalysis taught,

which is not that far from shamanic practice, the way to heal our fears and

neuroses is precisely to give those fears a name.

The cure passes through singing and

speaking.

Call them, talk to them, do not

leave them in their dangerous shadow, but pull them out of their lair to be

able to remove it, like the spirits blown away by the Filipino babaylan.

Recognizing our wounds is the only

way to become a healer of ourselves.

As Grace writes at the end of the

book, in the last lines, this path has not been absolutely easy, and twice she

fell ill from being in contact with the babaylan, without the doctors of

Western medicine being able to cure her. Because the reality of these healers

is that of the spirits, and they are not always benevolent: it can be extremely

dangerous to interact with them.

It is easy to be fascinated by the

magical and spectacular appearance of their rites, but what matters most is

“the state of one's heart, mind, and soul. In the end, we all need guidance and

encouragement to choose the path of love and compassion.”

I close with the splendid prayer of Bishop

Kenneth Cragg, with which Grace herself ends her introduction.

|

| Grace and me |

*Renamentaw, other name of the boat (biday)

Wow! I learned a lot. I did not know this part of Grace, i only thought she is just using her powerful voice in a very uniqie singing style because that is what she is good at, i was mistaken.

ReplyDeleteBtw, knowing Islam made it clearer to me what spirits are, so i am not surprised that this topic of yours about our old tradition, that is still in practice, have link to it.

I migrated to Palawan and now settled there, and during my last vacation i had this experience (approaching spiritualist). Sensitive to comment though. I just ask Allah(SWT) for guidance and forgiveness.

Thanks for this🌹

Yes, so I share the story of Babo Samida, anyway happy you like it. It's really big deep topic and the book is 400 pages, but this is just a blog 😊✌️

DeleteThe seek of harmony between body and spirit... which is the seat of emotion...the character...the soul...the courage...and determination that helps people to survive...to keep their way of life...and their beliefs.

ReplyDeleteYes, like Grace wrote last.. Path of love and compassion 🙏

Delete