|

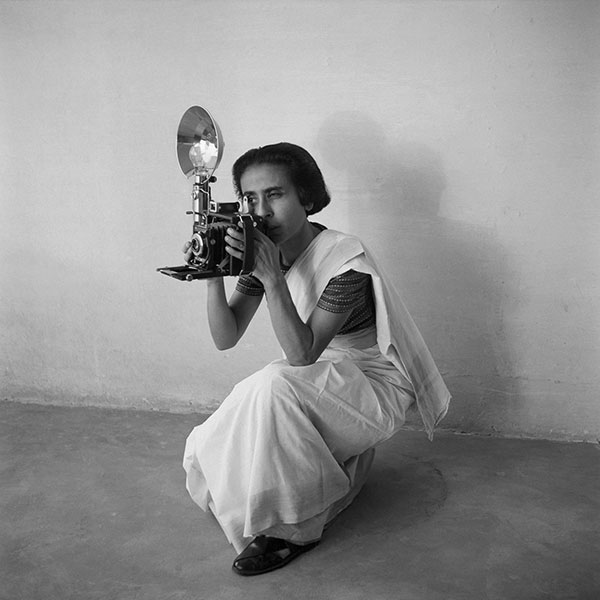

| Homai Vyarawalla ©Sam Panthaky /AFP via Getty Images |

Interesting stories are scattered around the world. There are people who enjoy great fame but are unknown to most. And sometimes their lives are compelling.

I want to tell you the story of “Dalda 13”. We

remain in India and in the female world.

After having met those who fought for education

and equal rights in the big Indian continent, let's go back to the thematic riverbed

for which this Blog was born, namely Photography.

I was very impressed by reading about the life of

Homai Vyarawalla, which is why I want to introduce you to her: a pioneer not

only as she was India's first female photojournalist, but in her career, she documented

the overthrow of British colonial rule.

And she was able to turn what appeared to

be a weakness to her advantage: being a woman with a camera in her hand.

Homai Vyarawalla was born on 9 December 1913 in

the western Indian state of Gujarat. Her family belonged to the small but

influential Parsi community of India.

She spent most of her childhood on the go

because her father was an actor in a traveling theatre group, until her family

soon moved to Mumbai (later Bombay), where she attended the JJ School of Art.

Homai came from a middle-class Parsi family, so

education was a priority for her. There were only six or seven girls in her

class, and she was the only one of the 36 students to finish the matriculation.

Dossabhai and Soonabhai Hathiram, Homai's

parents, were not well educated but wished their daughter to study English

further and enroll her at Grant Road High School in Tardeo. Homai's attempts at

education encountered a variety of obstacles, both social and otherwise: Homai

often moved house and walked long miles to school due to her family's poor

financial situation; moreover, like all the other girls in her village, she had

to endure the stigma during her menstrual periods, living in isolation for

their entire duration, preventing her from attending school as if it were a

temple not to be made impure.

After her matriculation, Homai continued her

education at St. Xavier's College, earning a degree in Economics.

In college, she met Manekshaw Vyarawalla, a freelance photographer, who would later marry her, introducing

Homai to photography.

|

| ©Homai Vyarawalla |

Vyarawalla began her career in the 1930s. At

the start of World War II, she had her first assignments for the Mumbai-based

magazine “The Illustrated Weekly of India”, in which she published many of her

most admired black and white images, albeit, in the early years of her career since Vyarawalla was unknown and was a woman, her photographs were published in

her husband's name.

Vyarawalla claimed that precisely because women

were not taken seriously as journalists, she was able to take high-quality

photographs, without the subjects of her photos giving her special attention:

“People were pretty Orthodox. They didn't want

women to move all over the place and when they saw me in a sari with the camera

walking around, they thought it was an extraordinary sight. At first, they

thought I was just messing with the camera, just to show off or something and

they didn't take me seriously. But this came back to my advantage because I

could also go to sensitive areas to take pictures and no one stopped me. So I

was able to take the best photos and post them. It wasn't until the photos were

posted that people realized how seriously I was working for that place.”

How to take advantage of what appeared to be an

obstacle or a humiliation. A good lesson.

Finally, her work began to get noticed

nationally, particularly after she moved to Delhi in 1942 to join British

Information Services. As a press photographer, she has portrayed many political

and national leaders in the period leading up to independence, including

Mohandas Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Indira Gandhi, and the

Nehru-Gandhi family.

Her education at the Sir JJ School of the Arts

in Mumbai, as well as the modernist images she saw in second-hand issues of

LIFE magazine, influenced her graphic sense. These inspirations can be seen in

her early portraits of common urban life and young modern women in Mumbai, but

as Vyarawalla was unknown and a woman, these were first published in

“Illustrated Weekly” and “Bombay Chronicle” under the name of her husband

Maneckshaw, or under the pseudonym “Dalda 13”, which came from her year of

birth, 1913, also at the age of 13 in which she met her husband and the license

plate of her first car read “DLD 13”.

|

| ©Homai Vyarawalla |

Despite her success at home and the long gallery of Indian leaders portrayed by Homai, she always remained in the background to Western photographers, as Sabeena Gadihoke, the curator of her photographic exhibitions, pointed out: “She was the only professional woman photojournalist in India during her time and her survival in a male-dominated field is all the more significant because the profession continues to exclude most women even today. Ironically, Western photojournalists who visited India such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Margaret Bourke-White have received more attention than their Indian contemporaries. In an already invisible history, Homai Vyarawalla’s presence as a woman was even more marginalized”. (Gadihoke, Sabeena, “INDIA IN FOCUS: CAMERA CHRONICLES OF HOMAI VYARAWALLA” The Alkazi Foundation for the Arts. Accessed January 26, 2020.)

In 1970, shortly after her husband's death,

Homai Vyarawalla decided to abandon photography, at the very height of her

fame, complaining about the “bad behavior” of the new generation of

photographers. She did not take a single photograph in the last 40-plus years

of her life: Homai Vyarawalla moved to Pilani, Rajasthan, with her only son,

Farouq, returning to Vadodara (formerly Baroda) in 1982. After her son died of

cancer in 1989, she lived alone in a small apartment in Baroda devoting all her

time to gardening.

In 2011, the year before her death, Homai

Vyarawalla received the Padma Vibhushan, the second-highest civilian award in

India.

In January 2012, Vyarawalla fell out of bed and

fractured a hip bone. Her neighbors helped her get to a hospital where she developed

respiratory complications; an interstitial lung disease led to her death on 15 January

2012.

When asked why she had given up her career as a

photographer at the height of her success, Homai replied:

“It was not worth it anymore. We had rules for

photographers; we even followed a dress code. We treated each other with

respect, like colleagues. But then, things changed for the worst. They were

only interested in making a few quick bucks; I didn't want to be part of the

crowd anymore”.

Shortly before the death, she donated her

collection of photographs to the Delhi-based “Alkazi Foundation for the Arts”

and, in 2010, in collaboration with the National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai

(NGMA), the foundation presented a retrospective of her work.

|

| Homai Vyarawalla. @indiahistorypics |

I believe that telling the story of this woman

in a sari with the Rolleiflex in her hand, little considered by the subjects

she portrayed, forced for a long time to sign her photos with her husband's

name and always in the shadow of the most famous Western photographers, is

important.

Because she shows great tenacity and deep

humility and dignity. There are not many who abandon what they loved most at

the peak of their success just because money stands out over ethical values.

This a great lesson that once again comes from a

woman in a profoundly male-dominated context.

This is also the India I love.

Thank you for sharing. Always love the life story about inspiring women

ReplyDelete👍

Thank you so much 🙏

DeleteWith lessons in life we should carry with us... Don't mind others, just do your thing. Sadly, at near end, she reached her maximum tolerance and gave up. She surely knew how and when to fight and when to give up, for self-peace.

ReplyDeleteNice one Stefano👏🌹

Totally agree ✌️

DeletePhotography is a love affair with life...but not all women know how to handle it...it is an honour if they can..lets cherish them.

ReplyDeleteThanksa lot

Delete