“Even a tree is never lonely for Strand,

he is the other tree.”

(Cesare Zavattini)

Let's go back to talking about

Photography.

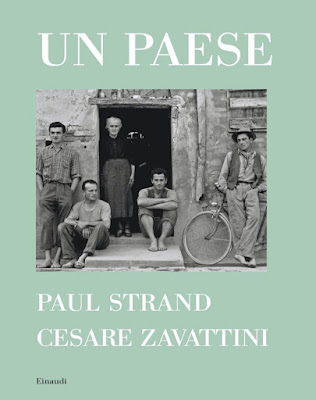

Thanks to a gift that was given to me for my birthday. The newly reprinted version of a classic from the 1950s, in a wonderful edition of Einaudi: “Un Paese”, by Paul Strand and Cesare Zavattini.

Paul Strand, born in New York in 1890 and died in Orgeval in 1976, was – together with Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston – among the greatest exponents of straight photography, which in the early twentieth century recovered the value of the technical and manual action of photography rather than the aestheticizing one of pictorialism which saw photography closer to art in itself, to painting. His extensive work spans some sixty years across America, Europe, and Africa, and he is regarded as one of the founding Masters of modern photography on par with Cartier-Bresson in Europe.

|

| Paul Strand © Martine Franck |

Cesare Zavattini, was born in

Luzzara, a small town in the province of Reggio Emilia, on 20 September 1902,

by Arturo Zavattini and Ida Giovanardi. He died in Rome on October 13, 1989.

With a multifaceted talent, he was an Italian screenwriter, journalist,

playwright, writer, poet, and painter, not also a comic scriptwriter.

Although for many he remains the

screenwriter of unforgettable masterpieces of Italian Neorealism, with over

eighty films to his credit. In 1934 he approached the world of cinema, devoting

himself passionately as a scriptwriter and screenwriter, and in 1939 he met

Vittorio De Sica, with whom he made about twenty films, including masterpieces

of Neorealism such as “Sciuscià” (1946), “Ladri di biciclette” (1948), and

“Miracle in Milan” (1951), but he also collaborated with Antonioni, Fellini,

Germi, Risi, Monicelli, Rossellini and other unforgettable Italian directors.

After his high school years in

Lazio, he returned to Emilia where he enrolled in the Law Faculty of the

University of Parma; his first job was that of tutor in the Maria Luigia

national boarding School in Parma: he was a teacher of Giovannino Guareschi,

Attilio Bertolucci and Pietro Bianchi.

At the beginning of 1930s, he

began his career as a prolific writer of novels and poems, he directed

satirical magazines and collaborated with publishing houses such as Rizzoli and

Mondadori.

In Luzzara he established the Prize

of the Naïfs in 1967 and gave rise to the first and only National Museum of

Naïves Arts.

Only to summarize his career and the

weight he still has in the Italian and world cultural heritage.

|

| Cesare Zavattini © Arturo Zavattini, 1988 |

The first time that Zavattini met

Strand was in 1949 in Perugia at the congress of filmmakers, but they did not

exchange a word because he was intimidated by his silence, then in Rome in

1952. What united them was precisely that neorealism, of which Zavattini was a

theorist, and whose spirit is so well described in these words that talks also

about the book: “A real charity of time of eyes of ears given to the facts, to

the people of own country.”

Much has been written about “Un Paese” (A Country). Of its genesis and its importance. Zavattini himself writes about it in the introduction.

At the beginning it was supposed to

be a film, then the first volume of a series that bore the same title as that

film project never made, “Italia mia” (My Italy), but in the end, it remained a

single volume which was also the first photographic book published in Italy, by

Einaudi, in April 1955, then translated by Aperture in 1997, in conjunction

with the Italian version of Alinari, still unavailable or with skyrocketing

prices.

As Maria Antonella Pellizzari tells

in the beautiful article “Un Paese (1955) et le défi de la culture de masse”,

the art historian Milton Brown had already accompanied his friend Paul Strand

and his wife Hazel on an initial tour of the Italian art in 1952, making them

admire the paintings of Caravaggio and Piero della Francesca, who was his favorite

painter.

From 1949 he had moved to France to

escape the attacks of Senator McCarthy's anti-communist policy, but since he

lived in America he had started to design a work entitled “A portrait of

village”, on the pure American soul, conceived during one of his travels in New

Mexico in the early 1930s, inspired by Edgar Lee Masters' “Spoon River

Anthology”.

His first photographic book, “Time

New England” (1950), was focused precisely on the search for the traditional

values of democracy in the American province.

Therefore the meeting with the

Italian writer was the trigger of a perfect creative explosion, united by the

common social inspiration and love for the people of their places.

The film critic Virgilio Tosi, who

knew the political commitment of the American photographer well, put them in

contact and from that moment the idea of “Un Paese” was born.

As Zavattini himself writes, in the

beginning – when Strand asked him which country to leave from – he would have

liked to close his eyes and point his finger at random on a point on the

geographical map of Italy, then he thought it was better to start from a

country that he knew well (so he believed), that is Luzzara, a small communist

paradise in Emilia-Romagna, a hotbed of partisan resistance between 1943-1944,

on the banks of the Po.

Strand, with his wife, worked there

for a month, accompanied by Valentino Lusetti, a farmer who knew English

because he had been a prisoner in America.

Thus writes Zavattini:

“Strand and his wife, she is from Massachusetts and he from New England, often consulted Luzzara's map, the mayor gave it to him, I had never consulted it and with them, I began to know my country, the names of the country districts, farmhouses: La Bruciata, La Samarote, Cornale. I didn't know before, what did I love then? If I saw a lumberjack passing by on his way to Po, I would say hastily: he goes to Po, and instead he goes to cut the first wood or the second wood or the third wood and his interests and thoughts are different in both cases.” (from “A Po lungo l’alzaia 18”, from the volume “I. An autobiography” edited by Paolo Nuzzi (Einaudi, 2002).

Paul Strand delivered 88 large-format photographs to Zavattini, using a Deardorff 8x10 camera, a 5x7 Graflex,

and, in some cases, for some panoramic views on the Luzzara market, a 35mm

Rectaflex.

“The montage of 'Un Paese' resembles a

film, with a

sequence of eighty-eight photographs masterfully selected by Strand,

and a text that features the unvarnished words of the villagers telling their

stories. Zavattini writes the introduction in the first person, retracing the

genesis of the book and his personal involvement. Two establishing shots of the

River Po lead smoothly into Luzzara as, in the text, a local man describes the

intimate experience of traveling across this landscape, watching a glowing sunset, and listening to roosters

and chickens.”

At the time in Luzzara, says

Zavattini, there were 100 illiterate people and 140 cars. In 1952, 205

emigrated and there were 209 immigrants. In the cemeteries, everyone had his

beautiful porcelain photograph and they seemed, in his eyes, all elderly even

if they died at 40 or 50, or at 48, like his father who had always considered

him old but now he was older than his deceased father.

The combination of Strand's powerful

photographs and Zavattini's essential words is poignant.

|

| “The Family”. Luzzara, 1953 © Paul Strand Archive / Aperture Foundation |

History has gone through the photo

entitled “The Family”, which has become an icon of all this work - not

surprisingly it is also the cover photo of the German version, in my

possession, of Aperture – Masters of Photography dedicated to Paul Strand,

published by Konemann in 1997.

A powerful and rigorous image which,

as Strand himself writes in a letter to Nancy Newhall, remains his first large

group portrait and the culmination of his social and formal concerns, with a

strong symmetry, with the elderly mother at the center and the detail of the

bare feet of the children.

Speaking is the mother, “I got married at 18 and had 15 children, 4 of whom died small. In '21 my husband Lusetti was beaten, then he was beaten again in 1926, I never knew the reason for all this, I only know that it was the cause of his death. In 1933 my husband died on Christmas Eve, leaving me in poverty with 8 sons and 3 daughters.”

Then she goes on to tell about her children who left for the war in France, Greece, Germany, Africa. “In '46 we were all together after 14 years of maternal pain. I dream of having a house of my own near a church to go there often.”

Financially the book was a failure, due to the high production costs that were an explicit request of Strand: of the thousand printed copies only a few of them were sold.

“In June 1955, soon after the release of Un Paese, Lusetti sent a letter to Strand where he described the villagers’ eager response and their access to the book at the local library. ‘It is a good book for communist propaganda,’ he wrote, but ‘there is a bad thing: the book is too expensive.' The cost of 3,000 lire corresponded to an average used bicycle – an annual salary ranged between 30,000 and 40,000 lire. If the content appeared ‘communist’ for its focus on the working classes, the book was financially not accessible to them” (Maria Antonella Pellizzari)

Despite the strong impact, the book did not have an easy life, and the photo “The Family” was also discarded in the famous exhibition “The Family of Man” in 1955.

However, as Pellizzari adds, regarding the part

written by Zavattini: “His text in Un Paese allowed problems and frustrations

to emerge. Young women expressed the wish not to get married to a farmer, and

children asked to go to school instead of minding the geese. The rosy communal

life, the workers’ cooperatives, and the joy of agriculture were interspersed

with comments about unemployment, the need for local industries, a hatred that the poor villagers experienced against the rich, and old people’s fears of dying

anonymously in a hospice.” (Maria Antonella Pellizzari)

Then everyone reads this book following their own

taste and mood, making their own reflections.

It was certainly pride and an honor for the whole

population of Luzzara. In October 2014, a delegation from the country was a

guest of the Philadelphia Museum of Art for the largest retrospective dedicated

to Strand ever made, which had its heart in those 88 photographs, crowning a

collaboration born in the year before, among the curators of the exhibition,

the American journalist and photographer David Maialetti and the Un Paese

Foundation.

The power to have an entire people recognized, for

generations and generations, in a single photo that portrays a family like many

others.

Some photo-stories struck me more than others, as is normal.

The first is that of some elderly people sitting and standing on the sidewalk of a street, under torn political posters and advertising signs. Six old men and an old woman crocheting, and a single line as text: “I want to die the same day that I'm no longer good at dressing and undressing myself.”

|

| © Paul Strand Archive / Aperture Foundation |

Common to this is the elderly woman sitting on the

chair who tells how she started the profession of cook at fourteen years and

was at the service of the greatest gentlemen of Luzzara. “It was as if I were

in my house, I loved them more than mine, then if I had to say how things went,

I don't know, one dies, another goes away from Luzzara and so since I turned 80

I am ended up in hospitalization, where I was treated well, but by a nickname, they call me the countess.”

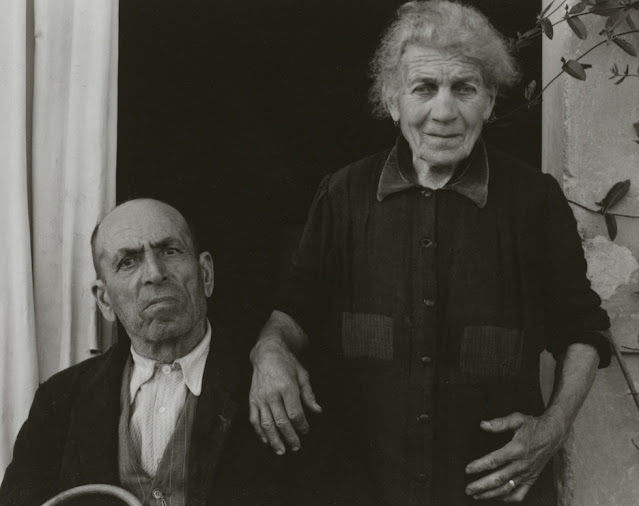

Or the husband who tells of his wife, next to him, who

has always worked the land with him, both 75 years old and four children.

“My wife is very cheap, she hardly ever used

shoes, not even in winter; she will have consumed four pairs of shoes in her

life, she also goes to town with shoes in hand. She has never been to the

cinema, she likes to dance and she would still dance.”

|

| © Paul Strand Archive / Aperture Foundation |

These are among my favorites, obviously according to my sensitivity and personal taste. Although ever, the one that completely captivated me and made me travel far with the imagination is one of the first images.

“She was one of the most beautiful and kindest girls,

my aunt told me that she met her and said: Hi, Paolina, where are you going?

but Paolina didn't answer anyone, my aunt thought she was going on a date even

if it was raining. We were around Christmas, towards evening, and she was going

to throw herself into the Po for love, they never found her and it seems that

she is in the hip of Paolina, which has been called della Paolina since

then, but with meters of sand above it because sand even arrives in one day and

makes an islet.”

|

| © Paul Strand Archive / Aperture Foundation |

This is a rare photograph taken with a Rolleiflex T by

Paul Strand's wife from the car during an inspection for what will become the

story of Pauline.

|

| © Hazel Kingsbury Strand, 1953. © Photographic Heritage of the Un Paese Foundation. |

The story that Zavattini tells of his land is truly poignant, there is no better term. He chisels every character and scene like little watercolors, with his talent as a screenwriter: like women who go to do laundry looking for the points of the Po where the water is clearer and pull up their skirts so as not to get it wet, but it always gets wet.

He reminded me of the poems of Cesare Pavese, the

verses collected in “Lavorare stanca”, “I only see hills and they fill the sky

and the earth...”

But also one of my favorite books by Ferdinando Scianna,

“Visti&Scritti” (Seen&Written), released in 2014 by Contrasto, where –

he also – converses and makes his photographs dialogue.

Here, I have often read about how Strand's images of

the people of Luzzara are symbolic. How they become the mirror of an entire

people, of Italy, if not of the poor and peasant classes that he already

carried in his heart from America.

So I think of the “Woman with the child” portrayed in

Licata da Scianna in 1967.

Also in this image, there is a reference to painting,

as happens for some of Strand's portraits.

Scianna starts from that photo by associating it with

the hundreds of Madonnas with Child who have nourished our eyes with their

iconography since catechism, forcing us – as photographers – to associate the

pictorial iconography of the Madonna with that image.

“But photography is not painting; it always combines

in the singular, it is not good at producing symbols.

It is her glory.

This is that woman and mother, not at all celestial,

perhaps with a shadow of a mustache, but so noble and proud of her child in the

poor house of Licata.” (Ferdinando Scianna)

This is how I see it. For me too, photographs always

combine with the singular. They are the individual stories of the people

portrayed.

It's Luzzara, with its people.

This takes nothing away, it is not a regression of

value, from a symbol to a simple signifier. On the contrary.

Here, in my opinion, lies all the charm and power of

this book.

Its glory, as Scianna says.

Strand's ability to have shown Zavattini what was

always in front of him. Because what is most difficult to know is precisely

what is in our eyes every day, until it disappears precisely because it no

longer surprises us.

Crossing miles and oceans to reach exotic and distant

places is the shortcut to be amazed at every step, to marvel at every corner.

It's another thing to be amazed by the places, faces, and colors that have accompanied us since our birth.

Zavattini got to know his country thanks to Strand's

photographs; everything he went through before he called ante-Strand.

Those faces of the elderly, of children, of peasants

revealed themselves for the first time to the writer, just like an epiphany,

literary critics would say.

Not as symbols but for themselves, for what they were,

and to which he gave the voice to complete the epiphany since it is precisely

the voice that is missing from the photograph.

The temptation to stand as a symbol is always strong,

it is part of human vanity and aspiration.

The charm of “Un Paese”, in my opinion, is instead its

invitation to love things as they are, to be close, and to know what is now

ordinary everyday life. Listening to those voices that one day will be lost and

no one will remember anymore.

To be that tree that makes the other tree not

solitary.

With the bitter regret of never knowing what Paolina's

face was like.

I thank Simone Terzi, of the Un Paese Foundation which manages the cultural heritage of the Municipality of Luzzara, for the documents and information related to the genesis of the book.

To know more: http://www.fondazioneunpaese.org/

The article,

quoted, by Maria Antonella Pellizzari: “Un Paese (1955) et le défi de la

culture de masse”, published in December 2012 on “études photographiques n. 30”

https://iphf.org/inductees/paul-strand/

Italian version

A poignant tribute. The way you described the charm of "Un Paese" and how we need it at this point... To appreciate what is in front of us so as not to be surprised and regretful of what we might have missed.

ReplyDeleteLucky people for having individuals who had much dedication to photograph, to record and relayed their ancestors' stories, an epiphany that made them whole.

You are good in always lacing your narrative with relevant information. Great job, as always.

Thanks a lot for your support 🙏

DeleteFrom what you shared...

ReplyDeleteI can understand that most photographers also have other creative art skills...and it turns out that a photographer has high creative art...with the talent award given.

Keep continue your determination to keep working...you are God's chosen one... thank you for sharing.

Thank you so much 👌

DeleteGood sharing,beautiful presentation

ReplyDeleteThank you so much ✌️

Delete“But photography is not painting; it always combines in the singular, it is not good at producing symbols."

ReplyDeleteAgree. Thanks for sharing. Now I understand a little more about photography.

"You don’t make a photograph just with a camera. You bring to the act of photography all the pictures you have seen, the books you have read, the music you have heard, the people you have loved." - Ansel Adams

Glad to know, thank you ✌️

Delete