Who knows how many times we've seen the Victory Sign done with the hand, and I'm the first to appreciate doing it in practically every shot of myself. An innocent gesture that I learned from Asian youngsters that have now evolved into something spontaneous and immediate.

Then, if someone asks why I do it, I'm not sure what to say: I just like it, it brings me joy, and it reminds me of selfies with children in Indonesian villages or Chinese ones in Rome; additionally, you don't always know where to put your hands when you're photographed.

We are bombarded with subtle gestures or statements in our daily lives.

This then is really minimal and

innocent.

It took a massive volume just bought

to give it meaning.

And what a meaning!

The book is titled “Photographies

East – The Camera and Its Histories in East and Southeast Asia” edited by

Rosalind C. Morris for the Duke University Press of London, released in 2009,

and collects some essays by anthropologists on the presence and meaning of the

act photography in Asia, since its origins, ranging between China, Japan, Indonesia,

Taiwan, and Thailand.

It is not the first book I have on

this topic, I have already mentioned previously the other volume dedicated to

the history of photography in Asia by Zhuang Wubin.

What these narratives have in common

is the premise of the impact that photography has had on various societies in

Asian countries.

Any study of this type always starts

from the role of photography as one of the tools of European and colonialist

aggression: from its earliest days, it has been the “sign of the foreign” and –

as such – one of the many types of equipment of the colonizing arsenal with which

Westerners have dominated in Asia.

However, it should be specified that

it's not a discourse that is reduced to the classic dichotomous distinction

between East and West, or between technological modernity and organic

primitivity, but the question is much more complex and goes deep into

photography itself; proof of this is that the skepticism – to the point of

actual terror – of the Asian populations was not aimed only at the white

colonizer holding the camera but at the tool itself, given that the same fear

and skepticism were also directed towards the first photographers Chinese.

In reality, the appearance of the

photographic act brought with it very symbolic and impacting themes, such as

the intimate relationship between photography and death; or between photography

and violence; the perception of the occult power inherent in technology; or the

link it has with the practices of political domination and suppression.

I remember, by the way, that most of

the time the first photographs taken in the East depicted the powerful kings of

the Thai or Chinese dynasties, or that it was precisely those sovereigns who

were the first to own the photographic equipment and dabble in that art, as

happened in Malaysia.

This is an absolutely fascinating

subject that I am spending a lot of time on and will come back to for sure in

the future.

Although, more than by the

historical digression, this time I was fascinated by the anthropological and

philosophical reading of these essays collected in the book.

Anyone who has been reading me for

some time knows how important philosophical reflection on the act of

photographing is for me. All the more so if all this is related to Asia.

Because what emerges overwhelmingly

from the different theses of this book is that Western colonialism has not

brought with it only the mechanical means of the camera but has also imposed

its different visions inherent in time, space, or large categories such as life

and death.

The idea of strangeness contained in

the discourse of photography has as its corollary the conception of the camera

as the origin of a fissure, which marks the separation between two very

different orientations of time: “It opens between an orientation to the past as

that which is cut off from its own future, and an orientation to the future as

the ideal form of the past”. (Rosalind C. Morris).

These two different directions of

time have inscribed in themselves mourning on the one hand and melancholy on

the other. All this happens thanks to the camera that is placed in the middle

of the time flow.

Obviously, this discourse is not

related only to Asia but is always valid when discussing the philosophical

value of the photographic act, from Barthes to Sontag: taking a photograph

drags with it the conflict between two different temporal modalities and

continually renews the drama of simultaneous disappearance and persistence.

The people portrayed in the

photographs we take every day, unconsciously, always become visible signs of an

absence which however persists over time, unlike our lives planted in finite

reality.

The problem arises when these

philosophical and cultural systems collide with Asian ones that are radically

different from ours.

Concepts such as time, the past,

death, the soul vary from country to country, from village to city.

Taking them for granted is a huge

mistake; but this is part of the presumption of “ideological colonialism” which

prompts us to think that in every part of the world we go, everyone must share

our ideas and our value systems.

|

Unknown photographer |

An example is an interesting

analysis made by Nickola Pazderic in his chapter entitled “Mysterious

Photographs”, in which he analyzes the strange phenomenon of “mysterious

photos”, lingyi zhaopian, which became popular in the 1990s in Taiwan.

This phenomenon is associated with

what the English called “spirit photographs” or “ghost photos” in the 1800s.

The nineties were for Taiwan the

transition point between a past marked by martial law established in 1949 with

the arrival of the Nationalist Party (KMT), remembered with fear as the baise

kongbu (white terror) under the tyranny of President Chiang Ching-Kuo,

which included the execution of 4,000 people, 8,000 imprisoned and over 20,000

persecuted. It was the period in which the president maintained his

authoritarian and criminal regime in the name of unity with China until the

liberation from this dictatorial climate with the return of the United Nations

in the late nineties and the proclamation of the identity of the island as

Taiwan.

What followed were the years of

economic boom, democracy, and the recognition of the island among the thirty

major economic and commercial powers in the world.

The late 1980s, thanks to the power

of economic development, infused new energies and dreams of consumerism and

imitation of the dominant Western models.

It is not easy to summarize the long

analysis of this article.

The author establishes a strong link

between these strange and uncanny photographs that often reported the presence

of ghosts imprinted in the negatives of the photographs and the incredible

success that wedding photography had, i.e. pre-wedding or wedding photographs,

which no couple could escape and which made hundreds of special photographic

studio flourish.

Photography as a necessary form for

the “indefinite perpetuation of the memory of the appearance of social

relations.”

On the one hand, there is the need,

impossible to decline in order to be socially accepted, to appear in the

photographs, on the other hand, there are the atavistic fears linked to

everything that revolves around the camera and the act of shooting.

Although it never comes to be an explicit admission, Taiwanese photography continues to have a mysterious and occult power.

|

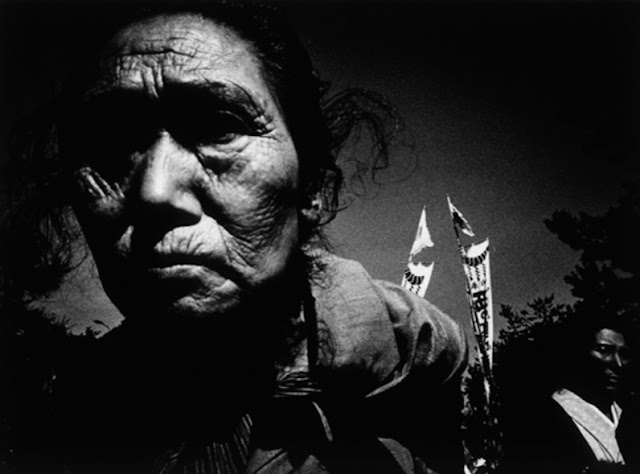

| ©Masatoshi Naito |

The anthropologist has recorded the

common opinion among people that the camera has the ability to capture energy

fields at low frequencies produced by both individuals and spirits (as

evidenced by “ghost photographs”).

Here we get to the heart of this

topic and the fascinating part of it for me.

For Taiwanese society, spontaneous

photography, what we call “street” photography, is the one that arouses the

most dismay and is judged negatively. Stealing a photo of a woman who is shopping,

walking, or talking unconsciously is considered “to steal shots” (toupai),

the use of which is that for the pure pleasure of those others.

Ironically, in the perception of

Taiwanese society, the awareness of being constantly filmed by video

surveillance cameras, even inside women's toilets, is more tolerable than being

photographed unconsciously.

Here I report this splendid metaphor

which is however perceived as real in the Taiwanese conception (and not only),

which helps to understand this strangeness well.

“It should be noted that spirits of

disorder and loss would remain invisible to most eyes were it not for the

camera. The device, however, is also marked by science and mystery because it captures

energy patterns and because its lens is conceived as yang (intrusive, ordering,

and male) while its negatives (fumian) are deemed yin (receptive,

disordering, and female). What is more, the phenomenological referents of black

holes, time tunnels, and spirit fields also share much in common with the ambivalent

ontology of the camera insofar as these signified theoretically hold the

universe together while threatening to suck the life out of it.” (N. Pazderic)

This perception of the camera helps

to better understand that fear of being photographed rather than being filmed

by cameras.

As an elderly Taiwanese told the

anthropologist, when he was still a boy in the village, it was a common opinion

among the country bumpkins (tubaozi), as he calls them, that he

absolutely had to avoid being photographed because the camera, with its flash,

would have captured the essence of the people portrayed, and that the films

inside the room, once pulled out, would have brought those souls with them.

Christian Metz writes it very well in his article “Photography and Fetish” (1990): “The snapshot, like death, is an instantaneous abduction of the object out of the world into another world, into another kind of time – unlike cinema, which replaces the object, after the act of appropriation, in an unfolding of time similar to that of life.”

|

©Masatoshi Naito |

Here then emerge the various forms

of resistance to this danger, of subtraction from the violence of photography.

I have read, for example, that it is

also an abiding Taiwanese belief – as I had already heard it said in Indonesia,

especially from women – that, given the occult power of photography, three

people should never pose in a single photo, since the imbalance of the order of

yin and yang would make the life of the subject in the center

shorter. Or that it is customary to huddle close when photographed for fear of

being left out of the group of people.

And, last but not least, returning

to our starting point, it is customary to make the “V” sign of victory with the

fingers of the hand precisely to vanquish the aggressive gaze of the camera.

All of this is obviously experienced with fun and excitement, but precisely

because this occult power of the lens is being resisted and exorcised.

It's amazing how certain innocent

attitudes can hide such thick plots of fears, superstitions and beliefs.

That this gesture then became common

in every part of the world and social class is undeniable, just as it is

certain that it has severed for many people that link to its initial meaning.

But that idea of the camera as the

mirror of yin and yang, with its masculine ordering power

projected outwards and the feminine receptive and carrier of disorder within

the negative that sucks the life and spits it out, with souls, like a black hole, I

think are among the strongest I've ever read.

Well, this is what I meant at the

beginning, which is the “colonial” habit of ignoring the profound differences

that separate us, which are not just those of language or religion.

The simple handling of a camera for

those who saw it for the first time and understood how it worked unleashed a

myriad of fears of which there is still a trace in these amusing and naive

attitudes.

This is a topic on which, of course,

I will return to write.

For now, I'll stop here and I hope it

helped you think once again about the power tied to a finger pressing a button.

As well as that of two fingers in a

V pointing towards the lens.

|

|

“Photographies East – The Camera and Its Histories in East and Southeast Asia”, edited by Rosalind C. Morris (Duke University Press, 2009)

This article caused me goosebumps from that creepy side of camera, the yang, and softness from the yin side.. The threesome superstitious belief made me smile because we have that too, until now, but my faith somewhat made me more open minded.

ReplyDeleteThis is a good topic and relatable. Who doesn't use cam nowadays?

Yes I think it is really interesting, to know how people think so different from us ✌️

DeleteMost people feel awkward when in front of camera...moreover with stranger photographer...they're not sure either want to smile or not...they think a lot in their head...while try to focus and pose.

ReplyDeleteBecause of that feeling...they just do whatever style will be to cover their shy.

As I know...V sign is very popular among Japanese (correct me if I am wrong) and also been warned must careful when make V sign...because people may see and use your finger print. (sigh)🤔🤔🤔

There are so many interesting topics! Must explore more and more ✌️

DeleteInteresting. Thank you

ReplyDeleteThank you so much ✌️

Delete