(Henri Michaux)

|

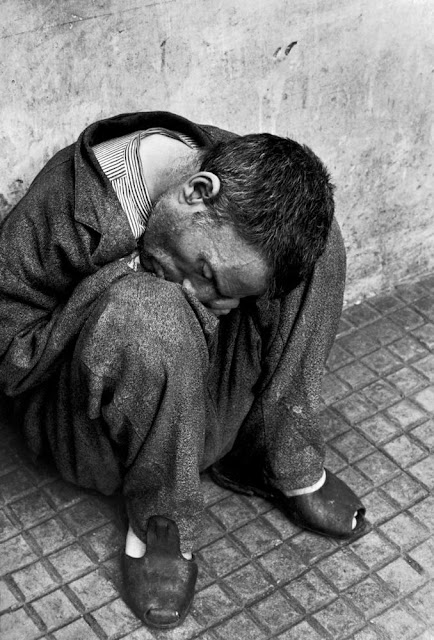

| Gianni Berengo Gardin. Provincial psychiatric hospital. Florence, 1968 |

Madness is a theme that has always

been close to my heart, ever since I was in school.

Many times I have written about it,

with poems and short stories.

Perhaps because I am fascinated by

the psychology and labyrinths of the human mind, and when those labyrinth paths

are darker and narrower, my interest is intensified.

Then loving art, one more reason

since not infrequently madness and creativity have courted each other and have

drawn on one another.

I still remember how excited and

euphoric I was when, a fresh first year university student (I still had the

intelligent habit of noting the date I bought the books: 14 \ 9 \ 1993), I

found the book by the psychiatrist Edward Podvoll, “The Seduction of Madness”,

hiding it as if I had stolen the forbidden apple in the garden of Eden.

“The splendor and chaos of the

psychotic mind in four extraordinary profiles of people who have traveled the

entire spiral of madness leaving a compelling and tremendous autobiographical

report,” reported the subtitle.

His point of view was incredibly

human, pointing out how the “medical” view of madness, as a simple rare event,

a brain failure that is feared and tends to isolate, is a false view of the

problem while in reality each of us, in every moment and phase of our

existence, can fall into madness – it is a human tragedy that also affects the

emotional aspect and not only the physiological, cerebral one.

But – most importantly – that

madness can be cured. It's an existential path, which is able to illuminate our

lives, give them a different meaning. Also artistic.

“Psychosis is a boundless dark

corner of the mind which, once illuminated, could change the view you have of

the entire room”.

Words that hit me deeply.

Coming to that book from the

classical Greek vision of madness that Plato described as follows:

“The madman is like a bird that

flutters and looks up, heedless of the world below.”

That book was the door that instead

opened onto that world of the “underground”, as Dostoevsky called it, not at

all light and fluttering.

Then came the psychology studies and

the degree, but until now, the interest in that mental underground has never

left me.

Indeed, these harsh months of forced

lockdown, uncertainty about the future, anxiety and depression, pushed me back

down. In my underground of “uncontrolled thoughts and altered sensations”,

although not yet dialoguing with them, which is the true mark of madness, as

Podvoll writes.

|

| Luciano D'Alessandro. Materdomini Asylum. Nocera Superiore (Salerno), 1965-68 |

I went back to this theme because a

few days ago I bought a beautiful photographic book, which I had been wooing

for a long time but too expensive, only to find it finally discounted at half

price, “The face of madness – A hundred years of images of pain.”

The book is the 430-page catalog of

an exhibition held in Reggio Emilia in 2006, and collects hundreds of images by

historical and famous photographers, from Scianna to Berengo Gardin, Alex

Majoli, Anders Petersen.

In asylums in Italy, Brazil, France,

Taiwan, Cuba...

The book also features a valuable

historical introduction by Sandro Parmiggiani.

It all begins with the infamous “Stultifera Navis”, The Ship of Fools, the satirical book in Alsatian German by Sebastian Brant, published in 1494, in which he told of this sort of Ark of the Fools put into the sea to remove madness from virtue of the people, even if it was a criticism of the vices of the society of the time. But, five hundred years later, Michel Foucault, entitled “Stultifera Navis” the first chapter of his famous essay “History of madness in the classical age”, will write as if it were a common practice to remove the “madmen” from the community of “normal”, entrusting them to seafarers:

“It often

happened that they were entrusted to boatmen: in Frankfurt, in 1399, some

sailors were commissioned to rid the city of a madman who was walking naked; in

the early 15th century a criminal madman is sent to Mainz in the same way.

Sometimes the sailors throw these uncomfortable passengers ashore even earlier

than they promised; this was witnessed by that blacksmith from Frankfurt, who

left twice and returned twice before being brought back to Kreuznach for good.

European cities have often had to see these ships of madmen land.” (Michel Foucault)

That ship, hypothetical or real it

was, landed in Reggio Emilia, where in 1536 the San Lazzaro Institute, born as

a leper hospital in 1217, became in effect the first asylum.

The island Narragonia, invented by

the writer Brant, where the madmen of the ship should have lived, became a real

place, in which to lock up the “disabled, decrepit, crippled, epileptic, deaf,

dumb, blind, paralytic”, or those who disturb the decorum of civil society.

The art critic and curator of the

exhibition Parmiggiani, born in that same place, still remembers the not

accidental location of San Lazzaro, far from the city and in a sort of no-man's

land, which reminded him of the black ghettos in the southern states United.

Racist-permeated places out of sight of decent people.

In 1821 it was officially called the

“General Establishment of the Casa de'Pazzi degli Estensi States”.

|

| Carla Cerati. Provincial psychiatric hospital. Gorizia, 1968 |

Everyone can have their own opinion

on asylums and their usefulness.

I consider Mario Tobino one of my

favorite Italian writers, and I advise those who do not know him to read the

series of his novels on Magliano, the asylum he directed in Lucca, until the

forced closure for the famous Basaglia Law n. 180 of May 1978.

In his novels and short stories

there is all the love and empathy for those “different” that he never stopped

considering as human beings. Especially in the novel “The last days of

Magliano”, from 1982, in which he bitterly describes the end of that journey

that lasted over forty years, recalling how that law caused, just in Lucca,

over one hundred deaths between homicides and suicides, as soon as the doors of

the asylum were closed forever, freeing the “madmen” in a society that never

accepted them, much less wanted them.

It is undeniable that the idea of

segregation and concealment of the “different” and disturbing is a topos

that crosses various spheres of Western society, and it would not be easy to

stem the flood of issues that would emerge. But the point of view of those who

have cared for and loved patients is also not irrelevant. Where children need

to walk accompanied, a loving hand that supports them is a thousand times

better than emptiness and looking after themselves.

Sure, many of the photographs in the

book are punched in the face, and some are truly terrible. But there are also

some soft, in which love and tenderness can be read.

|

| Ferdinando Scianna. “The Carnival Ball”. Udine psychiatric hospital. 1968 |

What interests me here, however, is

precisely the visual aspect, as a photographer.

Because if it is true that every

face is a question mark for the beholder, what relationship is created between

our eyes and these crazy faces?

The Egyptian writer and painter

Carole Naggar tries to answer this first question in her introductory paper

“Through a lens, obscurely”.

Naggar underlines how, from the very

beginning, the photograph of the madmen of San Lazzaro was a cold and

prejudicial distancing of the poor sick. It was called “photography of the

insane”, in which any person who showed physical or mental signs different from

the norm was portrayed with the same intention as the “exotic types of colonial

postcards”.

Photographers portrayed madmen with

the same horror with which peasants looked at witches in the Middle Ages.

Photographs in which there was no

intention of trying to penetrate those masks of pain, but which on the contrary

strengthened that typification, exalted it, as if to put a sidereal distance

between photographers, doctors, and the sick.

“The photo is the shield that

protects the doctor and the public, as if madness were a contagious disease

that the viewer could inadvertently catch himself if these representations were

not contained, framed by the frame of prejudices and the distance of a

pseudoscience.” Naggar writes.

Let's not forget that the first

photographic experiments also coincide with these photographs applied to

psychiatry.

The first representations of the mad

are found in the etchings by Alexander Morison (1826) and then in the

photographs collected in the three volumes of La Salpetrière (1877-80) and

Augusto Tebaldi (1884), forty years after the invention of the daguerreotype.

The Parisian hospital of La

Salpetrière will be the main place of the first photographs related to mental

illness, where the representation of the sick was experimented with the use of

electrodes applied to the facial muscles and then photographed those

expressions, constituting a “catalog of the various types of mental disorder”.

This is precisely what the Egyptian

writer reproached these early images for being a sample of “freaks”, without

any emotional empathy or intention of knowing their intimate pain, linking them

strongly to photos of the naked and skeletal bodies of Jews in the concentration

camps of Nazi.

Here comes the controversial

Lombroso, called Cesare (Verona, November 6, 1835 – Turin, October 19, 1909), a

famous Italian doctor, anthropologist, academic philosopher and jurist, defined

by some scholars as the father of modern criminology, exponent of positivism

and founder of criminal anthropology.

“His theories were based on the concept

of the criminal by birth, according to which the origin of criminal behavior

was inherent in the anatomical characteristics of the criminal, a person

physically different from the normal man as endowed with anomalies and

atavisms, which determined his social behavior deviant. Consequently, according

to him the inclination to crime was a hereditary pathology and the only useful

approach towards the criminal was the clinical-therapeutic one. Only in the

last part of his life did Lombroso also take into consideration environmental,

educational and social factors as competitors to the physical ones in

determining criminal behavior.” So it is written about him.

In 1898 he inaugurated a museum of

psychiatry and criminology in Turin (later called “Criminal Anthropology”).

“The

criminal is an atavistic being who reproduces on his own person the ferocious

instincts of primitive humanity and lower animals”.

Lombroso has gone down in history,

in a strongly criticized way, precisely because of this association between

physical peculiarities and mental states, not forgetting the association

between genius and madness. And crime.

We read again:

“From 1876

he divulged his anthropological theory of delinquency in the five successive

editions of ‘The Delinquent Man’, which he later expanded into a work in several volumes. Among the

leading physiognomy scholars, Lombroso measured the shape and size of the

skulls of many brigands killed and brought from Southern Italy to Piedmont,

concluding that the atavistic traits present brought back to primitive man.

Indeed, what developed was a new pseudoscience dealing with forensic

phrenology. He deduced that criminals carried anti-social traits from birth, by

inheritance, which today is considered completely unfounded. It should be noted

that Lombroso had developed the theory of atavism a year before the publication

of Darwin's The

Origin of Species.

The

characters that manifest atavism and degeneration would be physically explained

by the presence of characteristics such as the large mandibles, the strong

canines, the very developed median incisors to the detriment of the lateral

ones, the supernumerary or double-row teeth (as in snakes), the protruding

cheekbones, the prominent superciliary arches, the opening of the upper limbs longer

than the individual's stature, the prehensile feet, the cheek pouch, the

flattened nose, the prognathism, the bones of the skull in excess (as in the

Incas, in the Peruvians and Papuans) and other physical and skeletal anomalies

as well as functional characters different from those of advanced man; for

example, less sensitivity to pain, faster healing, greater visual accuracy and

dichromatopsia and also tattoos and accentuated laziness.”

|

| Tables by A. Tebaldi. Physiognomies and expressions studied in their deviations, 1884 |

Lombroso was perhaps among the most

famous and criticized in this area, accused of naive positivism, capable of

doing more damage than improvements in that scientific area.

But he was certainly not the only

one, indeed.

“Psychiatric photography” has always

been, since the very invention of photography, a powerful way to endorse the

theories of psychiatrists, in deep connection with physiognomy.

Precisely on the wave of positivism

and the irrefutable accuracy of science, psychiatrists used the new invention

to bring soul disorders to the surface of the faces, which otherwise would have

remained unknown and invisible: the portrait face of a patient became an

“example” of his diagnostic category.

The “domination of the gaze” sanctioned

by scientific power.

Diamond was among the first to set

up a photographic laboratory in his asylum in Springfield in 1851, improving

the calotype invented by Talbot in 1839. He was the first to theorize the

usefulness of introducing “photographic diagnosis”. Thus he stated:

“The

photographer captures with irrefutable precision the external manifestations of

every passion, as an authentic indication of the well-known correspondence that

binds the sick mind to the organs and features of the body.”

Because the problem with psychiatry

was that, unlike the other sciences, it was unable to “show” what it was

talking about, it did not have the material evidence that confirmed it as a

real science.

He needed an organ that “spoke”,

since the mind remained “mute” in its inner abyss: the face became that organ.

Before, and with much more vigor

than Lombroso, Johann Kaspar Lavater in the eighteenth century carried on these

theories taken up in the future also by our Lombroso.

“The face

is the summary and the result of the human form in general; and in it the flesh

is none other than the coloring that highlights the design.”

These were the bases on which the photography of madmen was founded, with all its prejudicial anomalies, since as Susan Sontag wrote so well: “What Wittgenstein said about words is valid for every photograph, that its meaning is the use,” that is photographs have their own weight according to the discourse in which they are inserted.

That said, I challenge each of you,

honestly, to deny that you have at least once in your life judged someone by

the face or body features. Were it not just that changed sidewalk to see

someone with a low forehead, teeth out, disheveled coming towards us. Or to

pray the elevator to open quickly because the man or woman with us has wild,

overly intense eyes.

The faces that we see in the

photographs, of children and smiling, docile people with sparkling eyes, make

us feel good. They reassure us. We never doubt their soul or sanity.

The different “ugly” faces, on the

other hand, suggest evil of the soul.

Looking at the faces of many serial

killers, rapists, pedophiles on television, how many of us exclaimed: “I

believe it, with that face!”

But as reported in these splendid introductions to the book, the faces of the first inmates in asylums were often rude peasants, women and men, most of the time illiterate, ignorant, hard workers of the land, who had only the misfortune of not being beautiful, like bourgeois society and scientists.

They could easily have been our

village great-grandparents and great-grandmothers.

We carry the atavism at the base of

Lombroso's criminal theories still within us, in the primitive and deep layers

of our fears and prejudices.

The photographs closest to us are

quite another thing, those of Scianna Berengo Gardin, Petersen...

In those who use photography to

communicate and know, in a different way than the scientists of the last

century, there is a desire to try to understand and never judge.

It also looking for moments of

tenderness, play, art, respect.

The camera is no longer a microscope

that divides and distances the “healthy” from the “crazy”, but rather brings us

closer to them, suggesting that madness is truly a tragedy of existence that

can happen to each of us, even to who has normal faces.

“The flesh of the face is none other

than the color that highlights the drawing,” wrote Lavater.

Stripped of its dominant and

scientific intentions, as well as racist, this sentence could also be read as a

poetic way of narrating the photographic portrait.

Because the meaning of the words is

in their use.

Petersen's blurry faces truly become

the color of the mind's drawings. The contrasts of blacks and whites the

narration of the inner darkness.

|

| Enzo Cei. Art exhibition in the former asylum of the work of the patients. Asylum of Maggiano (Lucca). 1999 |

Seeing these photographs, one after

the other, from the last century to the present day, becomes a journey into our

souls, who we are as human beings, how we “look”, and too often “judge”.

Therefore I like to conclude this long reflection with the magnificent words of Vittorino Andreoli, professor, doctor and famous psychologist and psychiatrist, on his over forty-five years of observation of madness, especially of the faces of madmen, because as Andreoli writes:

“A

dazzling light and sometimes thick fog envelops that face, the face of madness.

The rest

makes no sense, as if the fool had no body or became thin like a spider's antennae,

thin like a spider's thread. [...]

Getting

lost in the depths of the pupils that fall into the infinity of madness, among

the secrets of man, down, far from that surface on which time flows, while

there everything becomes slow and perhaps eternal.

And it is

difficult to emerge from the darkness. There is darkness in the background, the

immensity of darkness. There is silence and silence is dark, darker than

darkness. And a psychiatrist also becomes dark and erases everything that

lights up on the blackboard of knowledge that disappears down there.”

Like Photography. Camera obscura,

which develops its light from the shadow.

It dazzles, stuns with beauty. It brings to the surface the intimate design of our emotions, making it emerge from our immensity of darkness.

|

| Anders Petersen. ESPS, special section of the hospital for people with mental disorders. Stockholm, 1995 |

READ ALSO:

Michel Foucault: “History of Madness in the Classical Age” (BUR, 1992)

Mario Tobino: “For the ancient stairs” (Mondadori, 1992)

Mario Tobino: “The last days of Magliano” (Mondadori, 1983)

“The face of madness – One hundred years of images of pain” (SKIRA, 2006)

|

| |

I feel this topic is so closed to me.

ReplyDeleteAnd it gives a lot of new information to me too.

Interesting.

Later i want to read it again at home.

Thanks for sharing.

Enjoy the long reading with calm 😊

DeleteInteresting, 'crazy' article. It's sad that mad people once was discriminated n labelled by the 'ugly' face.

ReplyDelete"I challenge each of you, honestly, to deny that you have at least once in your life judged someone by the face or body features"

Challenge that I guess everyone can't deny it!

Totally agree 🙏

DeleteYa, because people always judge a book by its cover.

ReplyDelete" I challenge each of you, honestly, to deny that you have at least once in your life judged someone by the face or body features".

All of us did the same one time or more in our lives. Must think about this... Thanks 🙏

DeleteI am more interested in your brain and how you are able to penetrate the world of madness. Only beautiful expert genius mind can come up with this type of article, conclusive and decisive. You just wow me. A man like you is like a prism that can represent life in many forms. Salute.

ReplyDeleteSalute in madness. Anyway thanks... It's a topic interested me from young 🙂🙃

DeleteFuuhhhh...what a heavy article...really deep breath taking for me.

ReplyDeleteWell,I am not a psychiatrist...but I have experience with few of them...dealing with mental illness person...even being friend with them.

Among my students at school in the hospital...and few of workers at the cafe in the hospital.

From my observation..they were not originally mentally ill...they are normal human beings...but face uncontrollable emotional stress from the surrounding situation...causing them to panic easily and think hard...and at certain time feeling anxiety and having hallucination.

Thanks for your experience 🙏

Delete